a video essay by Max Tohline

2021

4 minutes

This project was inspired by the very fine collection of video essays on The Conversation (F. F. Coppola, 1974) produced by students of Johannes Binotto [here]. After I expressed my jealousy over not being a student in his course, Johannes graciously invited me to make an essay myself [here]. In the spirit of the other essays, it's without voice-over (tough for me), and I tried to keep it to 2:30. But it went to 4. Oh, well.

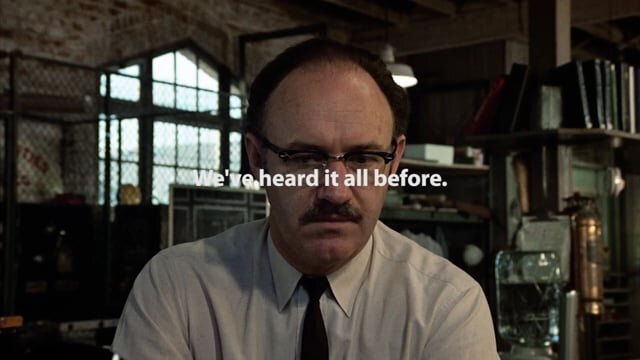

This video essay is a condensation of many thoughts I've had on The Conversation over the years, especially including a paper I gave at PCA/ACA in 2019 [here]. The first seeds of this idea came about a decade ago when I realized that halfway into the scene of Harry in the confessional, the acoustic properties of his voice suddenly change. Working from the hypothesis that we might be hearing his thoughts instead of his voice, I crafted a new interpretation of the film that puts Harry's Catholic faith at the center of the film.

Coppola himself remarked that the confessional is a form of surveillance (indeed, for Harry, everything involves surveillance; surveillance is his primary mode of subjectivity). But the scene must have also been deeply personal for both Coppola and Hackman, as Coppola's son plays the boy who crosses himself and Hackman's brother plays the priest who is barely seen through the grating. By including this semitransparent barrier, a visual motif associated with surveillance, the film seems to encourage us to find links between Christianity and the rest of the film's themes. Returning to the Bible with this in mind, it's not hard to imagine how Harry might read it: God, who hides himself [Psalm 13:1, Psalm 69:17, Psalm 89:46, etc], who often appears in a cloud [Exodus 24:15-16, Lamentations 3:44, Luke 9:34-35], but who can perceive hidden things [Matthew 6:6, Jeremiah 23:24]. Perhaps Harry, knowing that he's being heard, declines to confess his most significant sins.

Christianity acknowledges the remoteness and apparent hiddenness of God throughout scripture, but assures the faithful that at the end of time they will see not "a poor reflection, as in a mirror," but "face to face" with God. They will know fully, even as they are fully known. Such a message ought to be of great comfort to a bugger, but, as I interpret the film, only insofar as Harry remains confident that God exists. As I see it, the whole film can be read through the confessional scene. Up until then, Harry lived in a world where he surveilled other people. Where he was on the powerful side of the one-way glass. And whenever he visited the confessional, he was reminded that God was on the powerful side of a kind of cosmic one-way glass; that God was surveilling him. So he dared not speak his thoughts aloud. But in the second half of the film, the snoop gets robbed, the bugger gets bugged, and he can't find the microphone. But it's not the disempowerment that destroys Harry. He's used to God watching. What destroys him is that he can't find the bug. And as he finally gives in and tears into his Madonna, his epistemological crises spills over into a spiritual crisis. If he can't prove that they're listening... then how can he prove that God's listening?

Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/523275680

My thanks to Johannes Binotto for graciously listing this as one of the Best Video Essays of 2021 in the Sight and Sound poll.